The Middle Ages, spanning from the 5th to the late 15th century, is a period rich with linguistic evolution and diversity. This era bore witness to the profound impact of the Anglo-Saxon languages upon the tapestry of European linguistics and culture. Delving into this period allows us to understand how these Germanic languages, which traveled across the seas, formed the basis of Modern English and influenced the vernacular of an entire island.

Origin of the Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a group of early Germanic tribes, chiefly the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. They began migrating to the British Isles from their native lands in present-day Denmark and Northern Germany around the 5th century. Replacing the Romano-British cultures, they brought their languages, traditions, and societal norms.

What Did Anglo-Saxons Speak Before Old English?

Before the formation and dominance of Old English in the British Isles, the Anglo-Saxons—comprising primarily the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—spoke distinct Germanic languages in their homelands of present-day Denmark and northern Germany. These early Germanic dialects were part of a broader family of Indo-European languages.

These tribal languages, while separate, had similarities due to their shared Germanic roots. They featured a robust system of declensions, a rich array of strong verbs, and a penchant for compounding words. These linguistic features became foundational to Old English once the tribes migrated to Britain.

The migration and subsequent settlement led to an amalgamation of these dialects as the tribes intermingled, creating a more cohesive linguistic entity known as Old English or Anglo-Saxon. However, it’s essential to recognize that before their migration, the linguistic environment in their native lands was diverse. It was influenced by interactions with neighboring tribes and peoples, resulting in borrowings and linguistic exchanges.

Moreover, the British Isles already had its own languages, primarily Celtic and remnants of Latin from the Roman occupation. While Old English eventually dominated, it did assimilate some aspects of these pre-existing tongues, further enriching its tapestry. But at its core, the language of the Anglo-Saxons had deep Germanic roots, which they carried from their original homelands.

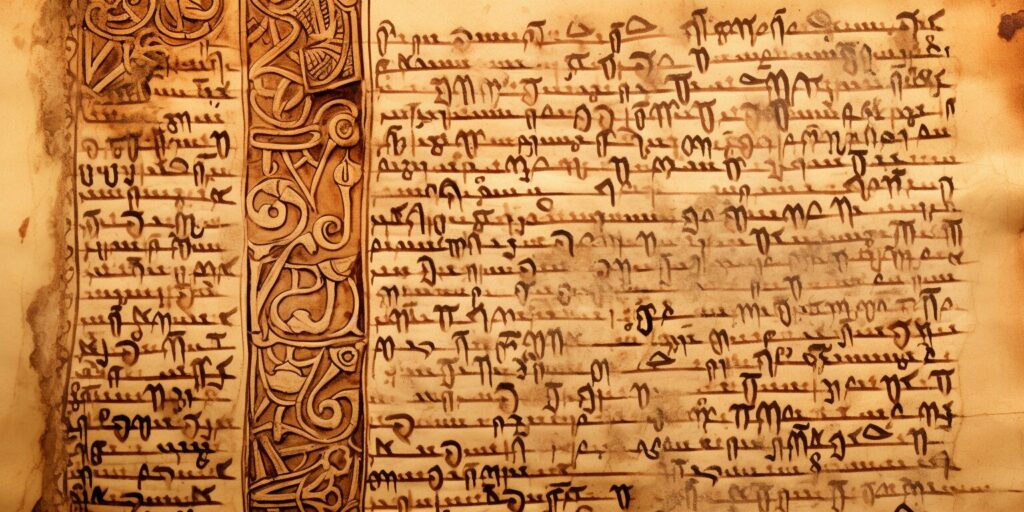

Anglo-Saxon Runic Inscriptions: The Futhorc Alphabet

The runes are an ancient alphabetic script, symbolic not only as a medium of communication but also deeply interwoven with the mythological and spiritual beliefs of the Germanic peoples. Before the full embrace of the Latin script by the Anglo-Saxons, they used a runic alphabet known as the Futhorc (or fuþorc), derived from the initial six letters of the system: “f,” “u,” “þ,” “o,” “r,” and “c.”

The Futhorc was an evolution of the Elder Futhark, an earlier runic system from continental Europe. As the Anglo-Saxons settled in the British Isles, their language and linguistic needs changed. Consequently, the Futhorc expanded to include characters better suited for the phonetics of Old English. From the original 24 runes of the Elder Futhark, the Futhorc grew to comprise between 28 to 33 runes, adjusting to the nuanced sounds of the Anglo-Saxon tongue.

These runes were more than just letters; they were potent symbols believed to hold magical properties. They adorned jewelry, amulets, and weapons as protective symbols. Runic inscriptions on stones served as memorials for the departed or marked territorial boundaries. They were also carved on wooden objects and manuscripts for various purposes, from the mundane to the mystical.

The advent of Christianity in the Anglo-Saxon realm saw a decline in the use of the Futhorc as the Latin alphabet became more predominant. Yet, the cultural and historical significance of these runic inscriptions remains undeniable. The Futhorc is a testament to the ingenuity of the Anglo-Saxons, adapting ancient symbols to echo the unique sounds and sentiments of their language.

The Evolution of Old English

Pre-Anglo-Saxon British Isles

Before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, the British Isles primarily spoke Old Celtic and Latin, with Latin being the lingua franca due to the Roman occupation. Still, the linguistic landscape underwent a dramatic shift with the Romans’ retreat and the Anglo-Saxon incursions.

Rise of the Anglo-Saxon Vernacular

As the Anglo-Saxons settled, their languages merged and evolved into what we now recognize as Old English. Although there were regional dialects like Mercian, West Saxon, Northumbrian, and Kentish, they all belonged to the broader umbrella of Old English.

Influence of Old Norse

By the 8th century, the Viking invasions introduced Old Norse into the linguistic mixture. This Scandinavian influence is evident in many modern English words like “sky,” “egg,” and “leg.” Additionally, the grammatical structures of the two languages meshed in various ways, simplifying some aspects of Old English.

Notable Literary Works

Old English produced some of the most iconic literary pieces, giving us insights into the ethos and spirit of the age.

Beowulf

Perhaps the most renowned Old English literary work, “Beowulf,” is an epic poem that narrates the heroic deeds of its titular character. Besides its riveting tale, “Beowulf” is a linguistic treasure trove, showcasing the language’s rich vocabulary and poetic devices.

The Exeter Book

This 10th-century anthology is one of the largest collections of Old English literature. Comprising riddles, elegies, and poems, it provides a window into the daily life, sentiments, and philosophies of the Anglo-Saxons.

Christian Influence and Latin Borrowings

The conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity in the late 6th and 7th centuries brought a significant infusion of Latin into Old English. Churches became centers of learning, and with Latin being the liturgical language, it was inevitable that it would permeate the vernacular. This influence is evident in religious, scholarly, and even everyday terms. Words like “monk,” “altar,” and “school” are borrowed from this period.

Norman Conquest and Everyday Use

The Norman Conquest in 1066 AD was not just a political and military takeover but a seismic event in the linguistic landscape of the British Isles. With the Normans’ arrival, Old Norman or Old French became the language of the elite – the monarchy, nobility, and the church. However, most of the populace, primarily of Anglo-Saxon descent, continued to converse in their native Old English.

Over the subsequent centuries, a linguistic dichotomy existed. In courts and churches, the Normans held sway with their language. Legal, religious, and scholarly documents bore a strong Norman influence. Yet, the Anglo-Saxon tongue lived on in homes, markets, and fields. Words related to farming, family, and basic daily life mostly retained their Old English origins. For instance, while the Normans introduced terms like “beef” (from French “boeuf”), the Anglo-Saxons continued using “cow.”

The interplay between these two languages eventually gave birth to Middle English, a hybrid tongue rich in nuance and vocabulary. While the elite conversed in Norman, the everyday speech of the Anglo-Saxons formed the backbone of English, ensuring its survival and evolution into the global language we recognize today.

Comparative Linguistics: Old English and Other Germanic Languages

Comparative linguistics provides an intriguing lens to understand the interconnectedness and evolution of languages. Old English holds a special place within the Germanic language family, showcasing a unique amalgamation of various linguistic influences while retaining its core Germanic structure.

Originating from the same Proto-Germanic roots, the early Germanic languages shared many phonetic, linguistic, and grammatical features. Old Norse, spoken by the Vikings; Old High German, from which modern German descends; and Old English were siblings in this linguistic family tree. These languages, while distinguishable, exhibited striking resemblances.

For instance, the Old English word “fæder,” Old Norse “faðir,” and Old High German “fater” all mean “father” in Modern English. Similarly, the verb “to sing” was “singan” in Old English, “singa” in Old Norse, and “singen” in Old High German. These lexical similarities underline their shared ancestry.

Grammatically, Old English and its Germanic counterparts were inflected languages, relying on a complex system of declensions to convey meaning. Case, gender, and number were essential components of their grammar, with each noun having multiple forms based on its function within a sentence.

Yet, Old English underwent unique transformations, especially after the Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain. While it retained its Germanic core, influences from Celtic languages and, later, the Norman French introduced variations that set it apart.

Comparative study reinforces the idea that languages are not isolated entities. They evolve, influenced by their kin and surroundings, shaping and reflecting the histories and cultures they traverse.

Middle English: Transition and Transformation

By the end of the 11th century, the Norman Conquest ushered in a new era of linguistic evolution. While the Normans spoke Old Norman or Old French, the general populace continued to speak Old English. Over time, these languages melded to give birth to Middle English.

Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales,” one of the most celebrated works from this period, epitomizes the richness of Middle English. While it retained many Old English lexicons, the grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation had significantly changed, primarily due to Norman’s influence.

The Legacy of the Anglo-Saxon Languages

The Anglo-Saxon languages, chiefly Old English, have bestowed an indelible legacy upon the fabric of Modern English. Despite centuries of linguistic evolution and foreign influences, the core of our contemporary language is rooted in the words and structures introduced by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Modern English, rich in synonyms, owes this wealth to its Anglo-Saxon base, often presenting words of Germanic and Latin or Norman origins side by side, such as “kingly” (Anglo-Saxon) and “royal” (Norman). Common words like “house,” “hand,” and “mother,” echo the everyday speech of our ancestors from over a millennium ago.

Furthermore, the Anglo-Saxon linguistic legacy is not limited to vocabulary. The foundational grammar, the penchant for compound words, and even our poetic sensibilities, with techniques like alliteration, are all gifts from this era. The resilience and adaptability of the Anglo-Saxon tongues also set a precedent for the assimilative nature of English, making it a mosaic of diverse linguistic influences. In essence, the words and structures we use today are like linguistic fossils, providing a window into a bygone era and showcasing the enduring impact of the Anglo-Saxons on our language.

Legacy in Toponyms: Anglo-Saxon Influence on Modern Place Names

The footprints of the Anglo-Saxons are still evident today, not just in the words we speak but also in the names of places we inhabit. Throughout England, toponyms (place names) bear testimony to the region’s Anglo-Saxon past, offering a linguistic map that traces the settlements, activities, and the natural landscape as perceived by its early inhabitants.

A plethora of town and village names end in “-ham,” an Old English word for “homestead” or “village,” such as Nottingham and Durham. The suffix “-ton” comes from “tūn,” meaning “farm” or “enclosure,” seen in places like Compton or Luton. Water bodies, like rivers or streams, were often designated with “-bourne” or “-burn,” derived from the Old English “burna,” as in the names Blackburn or Melbourne.

Similarly, natural landmarks also received their titles from Anglo-Saxon descriptors. The word “weald,” meaning “forest,” is seen in places like Cranbrook (meaning “crane’s brook”) or Harrow Weald. “Dun” or “don,” meaning “hill,” is evident in places such as Croydon.

These toponyms serve as linguistic relics, showcasing how the Anglo-Saxons interacted with their environment, designating landmarks, settlements, and natural features with names that communicated both function and form. Today, as we traverse these places, we are unwittingly journeying through a rich tapestry of history sewn together with the threads of the Anglo-Saxon lexicon.

What Anglo-Saxon Words Are Used in Modern English?

Modern English owes a significant portion of its lexicon to its Anglo-Saxon ancestors. These Old English roots are most evident in some of our most fundamental and frequently used words. Basic action verbs such as “run,” “eat,” “drink,” “sing,” and “think” hail from this era, grounding our language in its Germanic origins.

Many of our most elementary nouns also come from the Anglo-Saxons. Words like “house,” “child,” “man,” “woman,” “tree,” and “water” showcase the everyday life of people from over a millennium ago, making clear that the core components of our language and communication have remained remarkably consistent. Pronouns such as “he,” “she,” “it,” “they,” “us,” and “them” further underline this continuity.

It’s not just individual words but also certain linguistic structures that owe their existence to Anglo-Saxon sensibilities. For instance, our penchant for creating compound words, like “moonlight” or “toothbrush,” mirrors the Old English way of fusing words to convey nuanced meanings.

These foundational terms and structures are the bedrock upon which much of Modern English stands. They’re a testament to the lasting impact of the Anglo-Saxon tongue, reminding us that even in our rapidly evolving language, echoes of the past resonate strongly in our present-day conversations.

Final Thoughts

The journey of the Anglo-Saxon languages during the Middle Ages is a testament to the fluidity and dynamism of linguistic evolution. As we parse through Modern English, we find echoes of the past, remnants of the Anglo-Saxon spirit, and a language that has continually adapted, grown and thrived. The Middle Ages, with its tapestry of invasions, migrations, religious shifts, and cultural exchanges, stands as a pivotal period in shaping the linguistic destiny of the English language.